East Asian Studies (Chinese) at Cambridge: First Year

I matriculated for East Asian Studies (Chinese) at Churchill College, Cambridge in 2009. The course is four years, and I’m writing up my experiences of it year by year.

I matriculated for East Asian Studies (Chinese) at Churchill College, Cambridge in 2009. The course is four years, and I’m writing up my experiences of it year by year.

This page is on first year Chinese Studies (Part IA); I’ve only written about the course itself here, which is by no means everything. I’d say your course is about 40-50% of your student life at Cambridge, if not less.

Expectations

The largest wrong expectation that I had was that the course would be insanely hard. It’s hard, but not ridiculous. The other was that everyone in the class would be extremely intellectual and studious. We actually turned out to be a very normal mix of students and had a great time together (and still do).

I also expected that there would be a lot of competition in the class, and actually there was very little, especially by the end of first year. Everything was friendlier and more down-to-earth than I had expected.

Subjects

Seventy percent of our teaching time was spent on learning to speak, read and write modern Chinese. Just under twenty percent was spent on Classical Chinese, and about ten percent on East Asian History.

Modern Chinese

Our Modern Chinese course was built around a textbook and accompanying materials from 北京语言文化大学 (Beijing Language & Culture University), called [Modern Chinese - Chinese for Beginners](http://www.amazon.co.uk/gp/product/7561911173/ref=as_li_ss_tl?ie=UTF8&tag=easasistu-21&linkCode=as2&camp=1634&creative=19450&creativeASIN=7561911173" rel="external nofollow “Chinese for Beginners - Textbook - Amazon”). This textbook is, in a word, shit. The texts are all extremely dry and excruciatingly inoffensive, and the English used is riddled with mistakes.

The main problem with this textbook, though, is the way it sequences vocabulary. Numbers are given in different chapters in apparently random order, and we learnt the word 阿拉伯文画报 (“Arabic pictorial”) before 再见 (“goodbye”).

This became a running joke in the class, and almost everyone managed to squeeze the word “Arabic pictorial” into their oral exam at the end of the year. I’ll admit that I still don’t really know what an Arabic pictorial is, but I know I’ll never forget how to say it in Chinese.

Despite this, the awful textbook didn’t actually hold us back that much, as the teachers (see below) were wise enough not to rely on it too much. It was more of a structural guideline, and we spent the majority of our time with material the teachers created themselves.

From scratch?

The Chinese course at Cambridge is described as ab initio (from scratch) in the prospectus, so you’re not even expected to be able to say 你好 when you arrive. The faculty website even advises you not to begin studying before you start university on its preparatory reading page.

Some people followed this advice to the letter, and we dismayed to find that their new classmates included people who had lived in China or who had devoted considerable time to studying the language before. This made life pretty difficult for some and caused quite a lot of upset in the class.

However, the marks at the end of the year didn’t actually reflect previous knowledge at all. As far as I can see, the only predictors were attitude and effort.

Classical Chinese

The Classical Chinese course contained a lot of philosophical and cultural content as well as the language itself. Most of the first year Classical Chinese material was Confucian scholarly literature, starting with the Analects and then moving on to 孟子 (Mencius) and 荀子 (Xun Zi). We also had Daoist texts from 莊子 (Zhuang Zi) and 老子 (Lao Zi), such as 道德經 (the Dao De Jing), and some stuff from 孫子兵法 (Sun Zi’s Art of War).

The aim of the first year Classical Chinese course is to get students used to the language and its grammar, and to introduce them to the most famous texts. It also has a philosophical and cultural element looking at different strands of thought in Chinese history, which made up about twenty percent of the exam.

All of the material used in the first year course comes from real classical texts, so you’re plunged right into the actual thing. Other universities use example texts written for students to ease them into the language before moving on to the real stuff. I can’t say from experience which method is better, but it wasn’t too painful to start with genuine texts.

East Asian History

Regardless of language, all students of_ East Asian Studies_ at Cambridge take an East Asian History module in first year. It’s a real behemoth, covering the history of China, Japan and Korea (and a few other countries very briefly) from around 2000 bce to 1950 ce. That’s 3950 years of regional history in about 50 hours of teaching time.

Accordingly, it moves very quickly through huge swathes of history, only stopping on the most important and interesting areas to go into more detail.

“The course covers the history of East Asia thematically from the earliest times to the present, focusing on China, Japan and Korea. Students will read literature, historical monographs and primary sources to familiarize themselves with various types of historical evidence.”

AMES Undergraduate Handbook

One thing I wished I’d realised sooner is that you’re not expected to digest the whole lot and regurgitate it all in the exam. In fact, what’s expected of you is to select areas you can do well in and specialise in them, as the exam allows you to avoid areas you don’t want to write about.

Of course, you have to have some failsafe options in case your ideal questions don’t come up quite as you’d like. I ended up writing exclusively about China 1900-1950 in the exam, for three hours, and did fine.

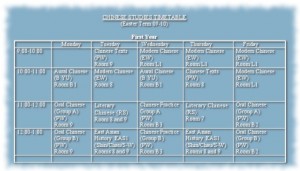

Our timetable

The weekly timetable for Chinese studies changes every term, but we always had our 17 class hours allocated as follows:

- Listening: 2 hours

- Oral: 2 hours

- Reading: 2 hours

- Literary Chinese: 2 hours

- ‘Chinese practice’ (free conversation class): 2 hours

- East Asian History: 2 hours

- ‘Modern Chinese’ (combined written / spoken class): 5 hours

Those were classes with all eighteen students. As well as those, we also had supervisions (two students, one teacher), for modern and classical Chinese for an hour each a week. In total we had 19 hours of teaching time a week.

We also had irregular supervisions for East Asian History, each of which was focused around a ~2500 word essay. These would be set three to four times a term.

Teaching staff

[caption id=”” align="alignright” caption="Dr Yuan, head of the Chinese Department”] [/caption]

[/caption]

All of our language teachers were native Chinese speakers from either mainland China or Taiwan. Most of them were excellent, and the rest were very good. They were particularly good at being strict in correcting our mistakes, and in having near-native English in order to clearly explain everything to a class of beginners. They are also inspiring and often very witty.

The Chinese teaching staff in the faculty at Cambridge are the main reason I tend to disagree with everyone who says “classes are no good” and so on. If the quality of teaching is high they can be fantastic. I think good quality classes are particularly effective in the early stages when it’s hard to know how to even approach a language.

The quality of Classical Chinese teaching was mixed though, depending on whether you were assigned to the faculty expert or a graduate student for your supervisions. Having said that, students from both groups got good marks in Classical; as always, it’s down to the student more than the teacher.

We had a wide range of teachers for the East Asian History module, frequently just for one lecture each. The course is extremely broad-ranging (too broad, in my view), so we had various experts and scholars come in to take this lecture twice a week. Many of these lecturers are pretty well known in the East Asian studies field.

Teaching methods

The teaching methods for modern Chinese were pretty standard. Read texts, discuss them, teacher asks students questions, students ask teacher questions, students do roleplays etc. We had dictation several times a week for all new characters learned. The humiliation of forgetting something in front of the class is quite a good motivator. Oral classes were taught in two groups, so the class size was only nine students.

The teaching methods for modern Chinese were pretty standard. Read texts, discuss them, teacher asks students questions, students ask teacher questions, students do roleplays etc. We had dictation several times a week for all new characters learned. The humiliation of forgetting something in front of the class is quite a good motivator. Oral classes were taught in two groups, so the class size was only nine students.

Our modern Chinese supervisions were extremely effective. There’s no room for slacking when there’s only two of you and the supervisor, and the hour-long sessions were intense. There’d usually be about three hours of preparation time necessary for each supervision, so the session itself would move very quickly, with quick-fire questions and rapid corrections.

Classical Chinese was also taught with a mix of lectures and supervisions, but was less intense than modern Chinese. We knew which texts were coming up for each class and it took about half an hour to prepare them. If you hadn’t prepared, though, it was pretty painful if you got asked a question.

East Asian History was taught in a classic university lecture format, with students taking notes and trying to revise from them before exams. Personally, I actually found it was better not to take notes, just pay attention, and then when it came to revision just re-research the material from books and online.

Difficulty & pace

The Chinese Studies course at Cambridge is fast-paced and difficult, but it’s not insurmountable. It just needs a lot of hours putting in. It’s probably a little bit more work than taking A-levels (British pre-university exams).

I remember one of our teachers at A-level saying “A-levels are actually the part of your education where you do the most work. You’ll find it’s a bit more relaxed at university.” This is probably why Cambridge and Oxford are seen as super-difficult environments - because they’re more stressful than A-levels. Actually they’re quite manageable, you just can’t slack off.

The most time-consuming module for most people was East Asian History; it was the one we worried about the most. I remember calculations being made that it was only 20%, so you could screw it up and maybe still get a first if your other modules were good.

We were stressed about it because of the volume of content - there was no way anybody could learn it all. As mentioned above, we were actually expected to focus on smaller areas within it, so it wasn’t anything like as bad as we originally thought.

After that, Classical Chinese was the most difficult, and was the one I put the most time into revising (hours and hours with a large Anki deck of every sentence we’d covered in class. At that point our knowledge of the language wasn’t good enough to comfortably figure out what an unseen sentence meant, so the best option seemed to be to memorise as much as possible.

The pace was such that by the end of the year no-one had much trouble reading the Chinese poem on the rock outside King’s, which was inscribed in 2008 to remember former King’s student 徐志摩.

Exams

Listening: 10%

This is a series of multiple choice questions with fast-moving audio that everyone listens to together (you can’t rewind it or anything). The questions are based around dialogues of increasing length, and there are quite a few trick questions (e.g. double negative questions with negative answers).

Oral: 10%

Amazingly, only 10% of our overall mark was based on our ability to actually speak Chinese. The oral exam had two parts. First you’re given a picture of a family in their living room, and you have 10 minutes to prepare a five-minute presentation about it. You also get asked questions about the picture for five minutes.

After that there’s ten minutes of free questions where the examiners try to stretch your Chinese by repeatedly asking similar questions so that you run out of good answers.

Modern Chinese Translation & Writing: 20%

This exam could be titled “production of written Chinese”. You’re tested on your grammar, writing ability and English → Chinese translation skills.

Modern Chinese Texts: 20%

This is basically a Chinese reading comprehension exam, with texts, comprehension questions and Chinese → English translation tasks.

Classical Chinese: 20%

The Classical Exam has three sections. First is a series of texts that were covered in class, so you have a chance to get 100% here if you’re fast and your memory is good. The second section is unseen sentences, usually with tricky grammar and weird logical constructions to try and trip you up. Finally, there are a few short essay questions on Chinese philosophy.

East Asian History: 20%

This is a classic history exam, with three hours to answer three questions. You choose one question from each of three groups, with a total of 15 options.

If you’ve chosen a good spread of areas to focus on, you should be able to just answer questions that you’ve studied intensively for. A large part of the skill here is being able to predict what sort of topics the exam is likely to ask about.

Criticisms

By the end of the year there were a few criticisms of the course from the class. The largest, and one that has been maintained in later years, is that there is no content about modern China. Just nothing post-Mao, until fourth year when there’s an elective module for it.

This seems like such a huge gap in knowledge for new sinologists from a world-class university. It should be compulsory right from first year, in my view.

Another thing I think would be useful is one or two hours a week with a native Chinese speaker who speaks absolutely no English. The idea would be that one or two students would meet with this person for a chat, pretty much. As there’s no option to speak English, plain awkwardness would get us speaking more Chinese in the early stages. I remember having this sort of thing for A-level French, and it was very effective.

As it was, I felt there was a bit too much English used in the Chinese teaching course, and not enough pressure to speak Chinese from day one. The more you speak the easier it gets, and at first you’ve just got to force yourself to do it, or have someone else force you.

I also think the course could make better use of technology. The audio lab is fairly archaic and underused. I’d like to see things like podcast subscriptions and various language learning software like Skritter being made available to students.

So that’s my round-up of first year Chinese Studies at Cambridge. Found it useful? Want to know something else? Want to add something? Share all in the comments.